Server Setup - How this page was delivered to you

An introduction

I’ve set up this blog with the intention of being able to write about technology which i find interesting, to that end, what better place to start than by showing how the infrastructure I use to serve this blog works? I’ll cover the setup from DNS resolution to the tool used to generate this html page.

Disclaimer

I am a rank amateur when it comes to web development, infrastructure, etc.. and my expertise is mostly in systems programming. Nothing here should be taken as best practise, or even good practise.

Hardware

Initially, my home server was a laptop purchased for around £25 on ebay, missing a few keys, bit gross, ex-corporate machine. It did the job for a while, and it’s nice for having a built-in keyboard, mouse, and video output, but it lacked performance and upgrade potential, and so I decided to build my current machine, featuring a Ryzen 7 1700, 16GB of DDR4 memory, a couple of 1TB SSDs, and 2x16TB hard drives, in a vintage home theatre PC case.

It sits in my living room on top of a bookshelf, and I have lofty goals to use it to drive my living room speakers and projector, allowing me to remove the chromecast.

other than that, I use a cheap TP-Link router wired straight into the WAN cable from my ISP. nothing to write home about, but gives me all the tools needed to run a home server.

DNS

DNS (Domain Name System) resolution is the act of turning a human-readable web address into a unique IP which can be used to locate a computer on the internet. There are many public DNS servers operated by various governments, private companies, and individuals which store translations between URLs and IP addresses.

When you enter a URL into your computer, it performs a DNS lookup by messaging a predetermined IP address (for example 4.4.4.4) and requesting to translate the URL into an IP, which it can then contact to request webpages, content, etc..

In an ideal world, my ISP would give me an IP address, and I would be able to register it with a DNS server, and have my URL always resolve to the correct IP. In practise, my ISP wants to discourage me from hosting a server on a residential internet connection, so whenever they detect an activity pattern that might be representative of a home server, they reassign me a new IP address.

There are many ways around this, but the simplest is to use a Dynamic DNS service. I use DuckDNS, which allows you to simply update your IP Address for a given URL either from a web service or automatically. I will go into more detail later when I cover docker containers, but needless to say, the worst case scenario would be that when my websites go down, I simply google “what is my IP address” and then paste that into DuckDNS’s website. In my lazier times, when the docker container malfunctions, I have regularly done this.

I plan to switch at some point to a more generic service where i can use a more custom URL, purely for vanity reasons.

Reverse proxy

So from the last paragraph, we’ve discovered how your web browser was able to use the url of this blog (https://blog.raffitc.duckdns.org) to locate my machine’s IP address on the internet. What next?

Your browser crafts a web packet along the lines of “give me the content stored at https://blog.raffitc.duckdns.org/posts/server-setup please?” and fires it towards my server. Since the web address contains https as its protocol, your web browser will know to request this via port 443 on my server.

So, the final step on the public internet is my ISP sending this request to port 443 of my public IP address (my router). My router is configured to send any packets on port 443 of its WAN port to the IP address of my server on the network (which is configured to always be static, never changes).

Once the packet is forwarded to port 443 of my server, a tool known as caddy which is bound to port 443 on the server consumes the request, and ‘handles it’ according to the rules i specified in its configuration.

I am using Caddy as what’s known as a ‘reverse proxy’ setup. in essence, this allows me to serve multiple discrete services with no connection to one-another via the same public port. I will gloss over for now how Caddy knows where to route this data, but its configuration typically looks like this:

https://service.raffitc.duckdns.org {

reverse_proxy service:1234

}

In this example, when Caddy receives a request targetted at https://service.raffitc.duckdns.org, it will redirect the packet to the service, on port 1234. This is interesting, because it implies that the service itself doesn’t need to use port 443, ie: doesn’t necessarily need to be https traffic, and that’s intentional, because Caddy provides the ability to automatically upgrade http traffic to https, signing the certificates and making the site display correctly on modern web browsers with protections against insecure sites.

The second thing to note is that https://service.raffitc.duckdns.org is the base url, which is effectively stripped out, and the request from Caddy to the service looks more like service:1234/posts/server-setup, for example. For most services this is ok, but for some others, if they need to generate an absolute URL for a hyperlink, they will need to be informed of the base url which Caddy has removed (Nextcloud is one such example).

Caddy can also serve static html content directly, like so:

https://blog.raffitc.duckdns.org {

root * /home/raffi/blog/public

file_server

}

which simply instructs caddy to present any of the web pages in ~/blog/public when requested.

Docker

Since I want to run multiple services simultaneously, It’s beneficial to somehow seperate them to prevent conflicts over network ports, IO, etc.. and to simplify maintenance. Docker exists somewhere between a program and a VM, abstracting many parts of program execution, but allowing it’s ‘containers’ to share the same syscalls for performance reasons.

Docker provides a configuration file type known as docker-compose files. Here is an example docker-compose file:

services:

speedtest:

container_name: speedtest

image: openspeedtest/latest

this instructs docker to pull a premade image from the internet, and construct a container called ‘speedtest’. It is also possible to map files and folders from your base machine to these containers.

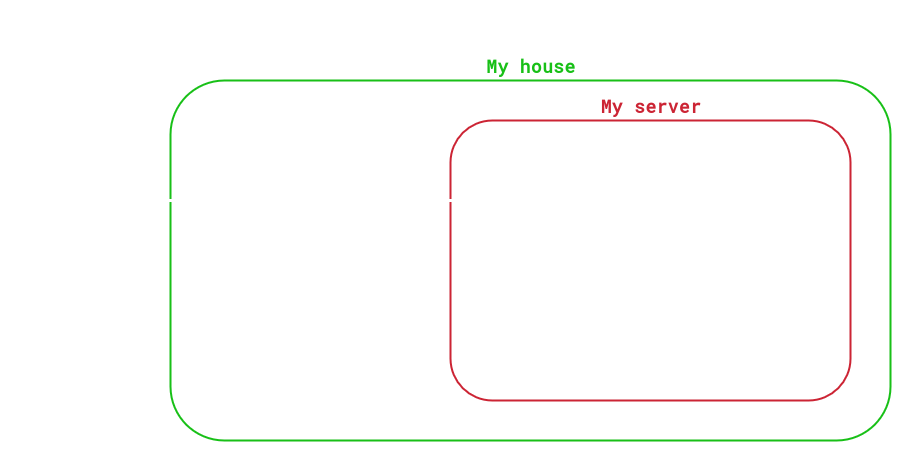

Caddy is also running inside a docker container, which allows a neat abstraction to keep all these other containers isolated from the outer world, as follows:

at the top of the docker-compose file, I have

networks:

web:

name: web

external: true

containers_internal:

name: containers_internal

external: false

driver: bridge

which creates two docker ’networks’, one of which (web) is able to communicate externally, whilst the other (containers_internal) cannot. Then I simply attach the following to all the containers in my configuration:

networks:

- containers_internal #if the container should be isolated

- web #if the container is to be exposed online

Caddy uses both, and games servers which don’t use http/s traffic are also exposed directly on the web, but all pages serving websites will get only the containers_internal tag.

This explains how Caddy can locate a service by name only. Docker has its own internal DNS server running on the computer, allowing Caddy to lookup the IP of other containers (typically in the 172.18.X.X range).